Applied Research in Education (Part III of III)

This is part 3 of a three-part series dedicated to Applied Research in Education. In what follows, I catalog and describe the differences between basic and applied research, and I describe the cyclical relationship between educational research and the practice of teaching. (Go to Part I, Go to Part II)

Differences between Basic and Applied Research

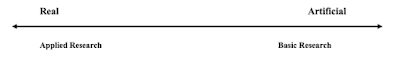

The easiest way to demonstrate the difference between basic and applied research is to look at the degree of reality and artificiality represented in each. To capture this difference, we might put “Basic Research” on a continuum that runs between Real and Artificial:

Figure 1: Mapping Research Styles on an Artificiality Continuum

As such, you might imagine a type of applied research that begins to resemble basic research. For example, a teacher might redesign their classroom for a school year in order to control for distractions so as to test the impact of a new activity. Doing so manipulates the typical classroom environment, but does so without moving the students down to some muted basement laboratory.

Below, a table provides a more useful comparison between basic and applied research.

Table 1: Comparing Basic and Applied Research

Applied Research | Basic Research | |

Control | Low | High |

Reliability | Low | High |

Validity | High | Low |

Artificiality | Real Life | Artificial Life |

Rigor | Low to High | Low to High |

Basic research will be more controlled, because care is taken to create conditions that keep away any unwanted variables, whereas applied researchers must confront the myriad variables that characterize real life. To that end, basic research will be more reliable, which means that a researcher can expect to get the same results were they to repeat their study (because the conditions are easily replicated). Applied researchers will have to understand their research within the context of what time of year it was conducted, who participated, what other events were going on, etc.

Basic research will, however, be less valid than applied research, because basic researchers must create artificial settings in which to carry out their studies. Then they must hope that these artificial settings accurately represent real life settings. Thus there is a gap between what is being tested in the laboratory and what the experiment hopes to represent. The bigger the gap, the weaker the validity. Applied research always takes place in real settings, so they have maximum validity.

The final dimension is rigor. Everybody loves or thinks they love rigorous research. Rigor means inflexibility or unbendingness, which I think is a rather strange feature to celebrate in research, particularly when humans are the subject. Rigor can be high or low in either format of research depending on how careful the researcher follows methodological procedures, guidelines, rules, protocols, etc.

The Relationship between Basic and Applied Research

I hope it is clear already that there is a direct relationship between basic and applied research. Both practices are included in a cycle that includes periods for practice, reflection, and hypothesizing. The question, however, is where the cycle begins. Does it begin in the laboratory, or does it begin in the classroom?

The scientists will argue that you have to understand the variables experimentally before you can hope to apply them. But the practitioners will argue back that you have to understand the classroom significance of variables before you can hope to test them.

I’ll leave their precise relationship up to you to figure out. But here are the components in the cycle, which is always ongoing.

Classroom Practice: Teachers teach or facilitate learning and learners learn.

Reflection: Teachers—the good ones, that is—think seriously about what seems to be working in their classrooms, what could be better, and what the major factors are that contribute to success and failure.

Hypothesis: Naturally, after reflecting, the same teacher will come up with an idea about how to reduce a problem or increase a success, and they will work out a strategy to implement their idea.

Basic Research: In a carefully controlled setting, trained researchers will take this hypothesis and design a study to test it. In conclusion, they will make a recommendation for what needs to happen in classrooms in the future.

Applied Research: Teachers will take the researcher recommendations and apply them in their—i.e., the teacher’s—classrooms, and see if it works in the real world.

Etc.

Note how practice informs research and research informs practice. Which comes first? I don’t really think the answer matters. What is important, in my opinion, is that there is an ongoing dialogue between the two.

Figure 2: Cycle of Research and its Application

In the world of clinical psychology, there is a rift that has formed between research and practice. The rift is so great that there are two separate doctoral degrees that are handed out, both doctorates of clinical psychology.

There is the Doctor of Psychology (Psy.D) in clinical psychology degree, which uses a practitioner model, during which students learn the art (and science) of clinical practice. The emphasis here is on using established methods of therapy to help people.

Then there is the Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in clinical psychology degree, which uses the scientist model, during which students learn the science (and art) of experimentation. The emphasis here is on designing randomized control trials. Sometimes, as is the case with Emory University in Atlanta, a PhD in clinical psychology does not produce licensed clinical psychologists who wish to help people; it produces scientists who wish to conduct research.

It is easy to imagine that it is during basic research that we learn what actually works and what doesn’t. Therefore teaching practice must be derived from basic research. But, in my opinion, it could just as easily be argued that the more significant role is played by the teachers—particularly when they are courageous to observe and identify some new problem or solution as it occurs in the classroom. Only then can basic research be carried out to try to better understand it.

Below I excerpt from a paper written by a well-known psychologist from decades ago who argued that applied psychologists offer more insights to experimental psychology than the reverse. It could be read by a teacher by replacing “psychologist” with “teacher.”

The excerpt is titled “The Illusion that Research Precedes Practice,” and it is taken from the article, “Humanistic Psychology: A New Breakthrough,” by the late American psychologist James Bugental. He writes,

We have long had the popular myth that the scientist develops knowledge and the engineer applies it. For this we could substitute that the researcher develops knowledge and the practitioner applies it. This has not been so in psychology, and it has never been so in physics and engineering either. More than one authority in the physical sciences has recognized that physics has received more contributions from engineering than it has given to engineering. Similarly, in clinically psychology, we have made more contributions to the body of psychological knowledge from the practitioner’s end than have been received by the practitioner from the research investigators. One need hardly elaborate this point beyond citing the work of Freud as an overriding example. Perhaps one additional highly important instance is the reintroduction of humanism into psychology. This reintroduction—which is the revitalizing, indeed the saving event of this period in the history of psychology—is in large part due to the contribution of clinical practice. More particularly it is in great part due to the experience of psychologists who have been engaged in the practice of psychotherapy. The names of the leaders in the field who are in the forefront of this development are the names of people who have had intensive immersion in the work of psychotherapy: Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow, Rollo May, Erich Fromm, and so on.

Again we can point to the influence of the model of the finite universe in which knowledge can be accumulated at random and eventually integrated and made available for the practitioner. Since we have disavowed this model, since we recognize that it is not veridical with the universe, then we must recognize that we need the practitioners’ contributions to highlight those areas of greatest significance socially. We need the practitioners’ testing of findings for pertinence and applicability; we need the practitioners’ contribution of proposing questions for research inquiry. (pp. 565-566)

Comments

Post a Comment