Applied Research in Education (Part I of III)

This is part 1 of a three-part series dedicated to Applied Research in Education. In what follows, I introduce Basic Research, which is the most formal style of education research. I end by describing a few of the forms that basic and applied research might take.

Applied research may be understood in contrast to basic research from which it derives.

Basic Research is the hallmark of modern science. With it, scientists and scholars test individual parts of the environment. The belief at the heart of basic research is that, one day in the distant future, scientists will have separated out and tested every individual part of the universe right on down to the smallest atom, and they will understand how all if it works. This belief is called “positivism.”

Educators are interested in many areas of basic research, such as learning, cognition, emotional intelligence, intelligence, motivation, relationships, mental health and well-being, human development, and so on. A huge area of basic research that has impacted educators for over a century is the behaviorist theory of learning. John Watson and Edward Thorndike knew that the laboratory experiments on rats, dogs, and pigeons might one day be applied to primary and secondary school classrooms, but the basic research that they and their colleagues conducted had to do with short-term and long-term acquisition of novel behaviors in rats, dogs, and pigeons (and other animals and insects as well).

Note how, with basic research, the subject matter (which is acquiring a novel behavior) is taken from an ordinary real-life context. A rat, which must learn to survive in New York City by hiding out in the darkness and eating scraps of food in the dumpster or left in the alleyway, is removed from its urban habitat and placed into a highly controlled setting such as a laboratory. The rat is taught how to press a lever or do jumping jacks or whatever the experimenter has decided will be its novel behavior. If the behavior is learned, then the experimenter believes that they can say something about how to teach animals to learn a brand new behavior.

This basic research is published, and in the article the experimenter concludes by saying something like this: “Now, if elementary school teachers can do with children as I have done with the rat who does jumping jacks for me whenever it pleases me, then elementary school teachers will succeed at teaching their children how to multiply integers.”

In this example, the rat psychologist tests a hypothesis about jumping jacks in rodents and then suggests that it could work with children who are learning their multiplication tables. In order to see if it does, indeed, work on children, it must be applied in a real setting, such as an elementary school classroom.

Educators might be interested in basic research about autism or ADHD, aggression, trauma, memory, and so on. However, in order to see if the basic research is of any importance to what happens in the classroom, it must be applied in the classroom.

The Subdivided Student

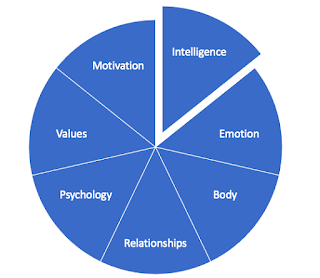

Figure 1. The Subdivided Student

In conducting basic research, the scientist must be careful to isolate individual factors for testing. In order to see, for example, whether a new teaching strategy has a positive impact on student psychological well-being, the scientist must take care not to allow classroom snacks, Spring Break vacation, a high school dance, lunchtime feuds, pep rallies, and so on to impact the experiment. Therefore, basic research must be conducted in highly controlled environments. These are the sort of environments that teachers and students will never encounter in real life situations.

In the above diagram, basic research begins with the assumption that it is possible to look at and measure only intelligence without getting any interference from emotion or students’ religion or values. Consequently, basic research takes as its subject an artificial student—the so called “average student.”

The brings about the myth of the subdivided student. In this myth, it is believed that the student can be broken down into a series of separate dimensions. When a researcher says that they are interested in studying student motivation, for example, they believe that they can isolate motivation and prevent cross-contamination with student emotion, student relationships, or student values—that these other dimensions of who the student is won’t mess up the results.

Forms of Research

There are many forms of basic and applied research. The exemplar is the experiment, which maximizes control. In an experiment, only one variable is manipulated while all other variables remain constant. This means that the experimenter is confident saying that the results stem from the variable being tested, and not any other unforeseen variables. Looking at Figure 1, this means that steps must be taken in order to ensure that all the other slices of the pie are kept from messing up (i.e., confounding) the results.

Experiments can be designed for basic or applied research. The main difference is how closely the research settings match the real-life settings of a classroom. Autonomy-Supportive Teaching, which is a series of teaching strategies that increase students’ psychological well-being, stems from the basic research in Self-Determination Theory. AST is SDT when applied to the classroom. Hundreds of these applied studies have been conducted using randomized control trials. These are very difficult to conduct as applied research, because they have to be organized around real school years with real students and real teachers who are interacting in real time. Still, enough care can be taken in order to make the applied research an experiment.

In the classroom, however, a high level of control can never be expected. Imagine trying to test the impact of a teaching strategy during a school year that is interrupted by a global pandemic! Students, who are often the participants of education studies, are subjected to thousands of outside influences—parents, siblings, friends, schedules, sports and extra-curricular activities, diet, recess and vacation, time of day, sleep quality and duration, emotional support, etc., etc. A new experiment would have to be designed in order to test the impact that each of these variables has on learning, as well as how they interact.

Some researchers accept that control is going to be impossible to maintain in an experiment—whether the goal is a bit of applied research or basic research. They might instead try to design a quasi-experiment, which attempts to test the relationship between variables without trying to control the breadth of unpredictable life factors that will inevitably confuse and confound the results of the study. Even still, the quasi-experimenter is assuming that it is possible to say something meaningful about a single aspect of the learning environment, such as whether 5-minute breaks every hour are more useful than 10-minute breaks every two hours. This detail of break duration is taken out of its context within an ordinary school day, and it is assumed that doing so will not meaningfully change the significance of the break or school day.

Quasi-experiments can be conducted in an applied manner (by introducing a new five-minute break during the two-hour math lesson), or it can be conducted as basic research, where a nonrandomized sample of 100 students are invited to a neutral location to test the impact that five-minute breaks have on ocular sensitivity. (I have chosen an intentionally obscure dependent variable.)

There are many subcategories of research, but I’m just going to name three broad ones. The first two have already been described (experimental and quasi-experimental; to this I could add correlational, but I believe that correlational study results are too easily misinterpreted, and with great consequence). The third subcategory of research is qualitative or descriptive research. These studies are less interested in explaining why, for example, a hostile classroom climate affects student mood, and are more interested in what a hostile classroom climate is like from the vantage point of students. This sort of researcher might ask students, “So, Mr. Toadvine is a very kind and considerate teacher. How do you feel when you are in his classroom?” Students are likely to describe all sorts of things—only some of which are related directly to classroom climate. Therefore, this kind of research does a better job of approximating a real classroom experience—that is to say, it represents the wide variability of personalities, expectations, backgrounds, and so on that students and teachers can expect to find.

But even qualitative research that is conducted in this spirit is a little bit contrived. In this example, the researcher believes that they can better understand some mysterious factor called “classroom climate.” They believe that this dimension exists separately from, say, the actual thermostat-regulated climate in the classroom.

Move on to Part II of Applied Research in Education

Comments

Post a Comment