Carl Rogers, the Radical Educator, Part I: His Earliest Influences

When Carl Rogers was 85, his writing and his life and his relationships would have a significant impact on a one-year-old. That one-year-old was me. Of course, I didn’t know it at the time, and neither did he.

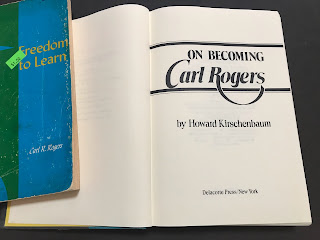

In case you did not train at a humanistic psychology school, Carl Rogers was the therapist responsible for “client-centered therapy” and “unconditional positive regard.” His book Freedom To Learn is all about how to create classroom conditions that allow students to teach themselves. It has influenced me greater than any other book on teaching. In the last 10 years I have probably read it 12 times.

In this post (and maybe 10 subsequent posts) I will introduce some of Rogers’s ideas about being a facilitator of learning. I am currently working on a book, which is tentatively titled FORGETTING HOW TO TEACH, where I describe what that might look like in a university classroom in 2022.

On to the bit about Rogers:

Rogers grew up in a conservative Christian home in the Midwest, just like I would 85 years later. He went away to college interested in becoming a reverend, just like would 85 years later. He went to seminary, which is where our paths depart.

While at Union Theological Seminary, Rogers encountered the progressive educational ideas of John Dewey and William Heard Kilpatrick.

Despite reading his biography many times, I had never appreciated the impact of these educational philosophies on Rogers’s perspective. I always thought that he had evolved his pedagogy from his therapy. Evidently I was wrong. Even before leaving seminary, Rogers had already adopted his own radical approach to teaching, which he put to work in a nearby church-based school. Here was his recommendation for the training of religious teachers at that school: “Put not your trust in Teacher Training Courses. By beginning with the immediate problems of the teachers, by sharing experiences between the new teachers and those who have been longer at it, and by developing further the interest which all have in certain common problems, I believe one will accomplish more actual education than through a formal course.” (All quotes taken from On Becoming Carl Rogers, the biography written by Howard Kirschenbaum.)

This has been my opinion, too. But, of course, Inhave been influenced by Rogers, so that really isn’t a surprise. As a fellow of my school’s Center for Faculty Excellence, which helps train and mentor new faculty, I had the opportunity to meet with 15 new professors earlier this year. I had been asked by the director to present something about developing a research agenda. This was probably because research was the leading reason faculty were denied tenure over the previous few years.

I treated the seminar like I do my ordinary classes: I recorded a 40-minute “how to develop a research agenda” video, and distributed it to the participants with the instructions to watch it only if they were interested in developing a research agenda and thought it might be useful. When I met with the new faculty, I invited them to share what they perceived as the most significant problems they were facing during their first year at the university. (I was the "teacher who had been longer at it" from Rogers's description.) Research did not come up. What we spent most of the hour talking about was how significantly they had had to adjust their expectations for teaching our students, who have historically low levels of academic preparation.

The new professors approached the topic of needing to adjust expectations as if it was a cottonmouth hiding in the barn. (If you have never had the experience of suspecting that a cottonmouth was hiding in your barn, then this is how you would approach it: with apprehension and care.) Beneath their concern was anxiety about doing a good job, being prepared, seeming optimistic, and so on. That is to say, not only were they struggling with this problem, but they also felt like they might get themselves into trouble by sharing it. Within about ten minutes, the apprehension had lifted and they were able to state their concerns, which everybody seemed to share. It was cathartic.

Rogers and his classmates began asking serious questions about what it meant to help other people, and whether it was possible to do so from a particular religious orientation. You know, the sorts of questions that make seminary faculty uncomfortable, but which, nevertheless, need to be asked. They asked if it would be possible to take a course designed by students—one without any faculty intrusion. He writes:

[We] felt that ideas were being fed to us and that we were not having an opportunity to discuss the religious and philosophical issues which most deeply concerned us. We wanted to explore our own questions and doubts and find out where they led. We petitioned the administration that we be allowed to set up a seminar (for credit!) in which there would be no instructor and in which the curriculum would be composed of our own questions. The seminary was understandably perplexed by this request but they granted our petition. The only restriction was that in the interest of the Seminary a young instructor was to sit in on the course but to take no part in it unless we wished him to be active.

Rogers goes on to explain how the seminar was deeply rewarding. He and his classmates eventually thought their way right out of seminary and into adjacent fields—Sociology, Psychology, and so on. Rogers ended up at Columbia Teacher’s College where he would train to become a therapist.

Comments

Post a Comment